-2024届高三英语二轮复习Show, Don’t Tell 读后续写技巧指导课件(共88张PPT)

文档属性

| 名称 | -2024届高三英语二轮复习Show, Don’t Tell 读后续写技巧指导课件(共88张PPT) |

|

|

| 格式 | pptx | ||

| 文件大小 | 669.8KB | ||

| 资源类型 | 教案 | ||

| 版本资源 | 通用版 | ||

| 科目 | 英语 | ||

| 更新时间 | 2024-03-25 00:00:00 | ||

图片预览

文档简介

(共88张PPT)

Show, Don’t Tell

How to write vivid descriptions, handle backstory, and describe your characters’ emotions

Definition

What show, don’t tell means

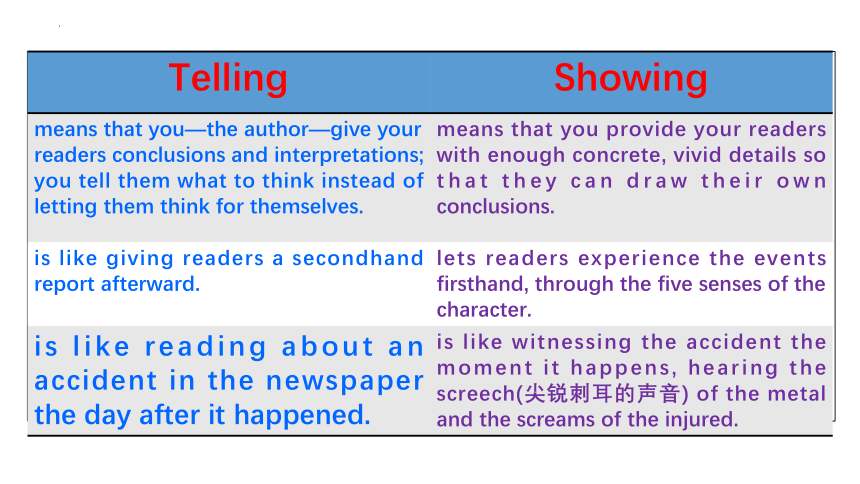

Telling Showing

means that you—the author—give your readers conclusions and interpretations; you tell them what to think instead of letting them think for themselves. means that you provide your readers with enough concrete, vivid details so that they can draw their own conclusions.

is like giving readers a secondhand report afterward. lets readers experience the events firsthand, through the five senses of the character.

is like reading about an accident in the newspaper the day after it happened. is like witnessing the accident the moment it happens, hearing the screech(尖锐刺耳的声音) of the metal and the screams of the injured.

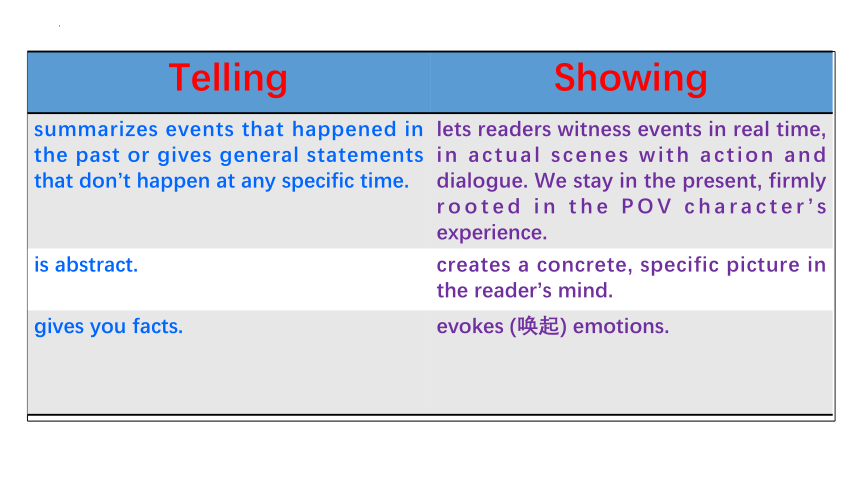

Telling Showing

summarizes events that happened in the past or gives general statements that don’t happen at any specific time. lets readers witness events in real time, in actual scenes with action and dialogue. We stay in the present, firmly rooted in the POV character’s experience.

is abstract. creates a concrete, specific picture in the reader’s mind.

gives you facts. evokes (唤起) emotions.

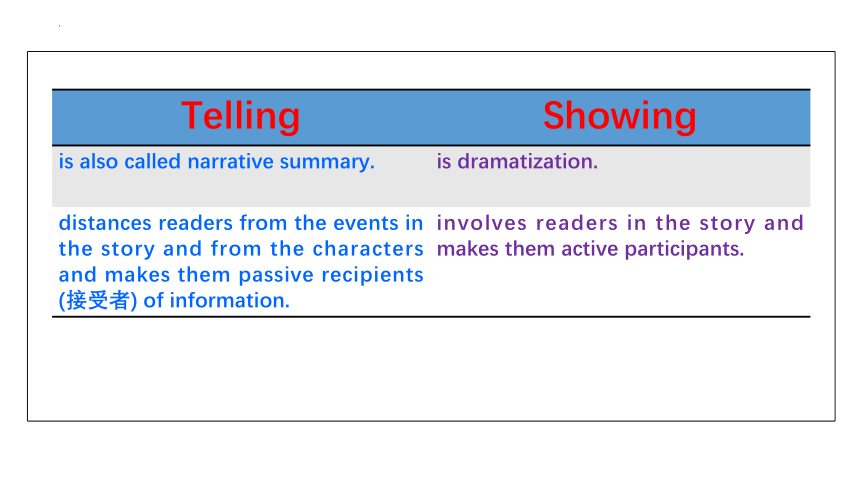

Telling Showing

is also called narrative summary. is dramatization.

distances readers from the events in the story and from the characters and makes them passive recipients (接受者) of information. involves readers in the story and makes them active participants.

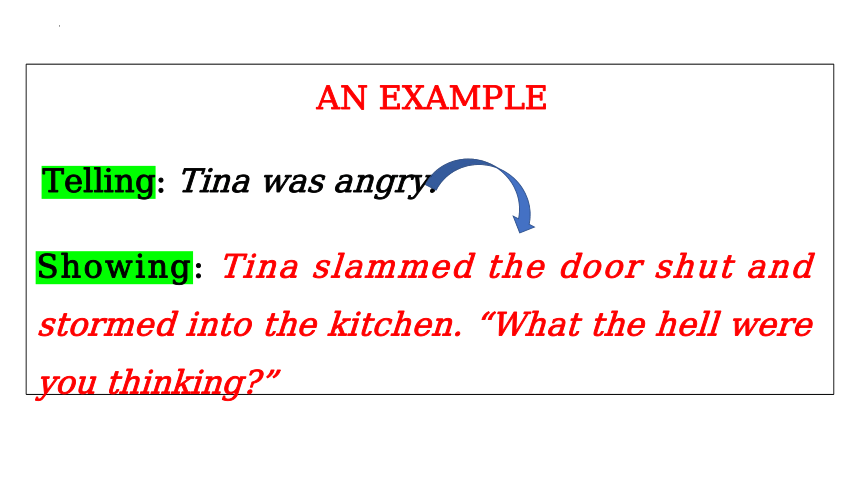

AN EXAMPLE

Telling: Tina was angry.

Showing: Tina slammed the door shut and stormed into the kitchen. “What the hell were you thinking ”

Nine red flags for telling

How to tell when you’re telling

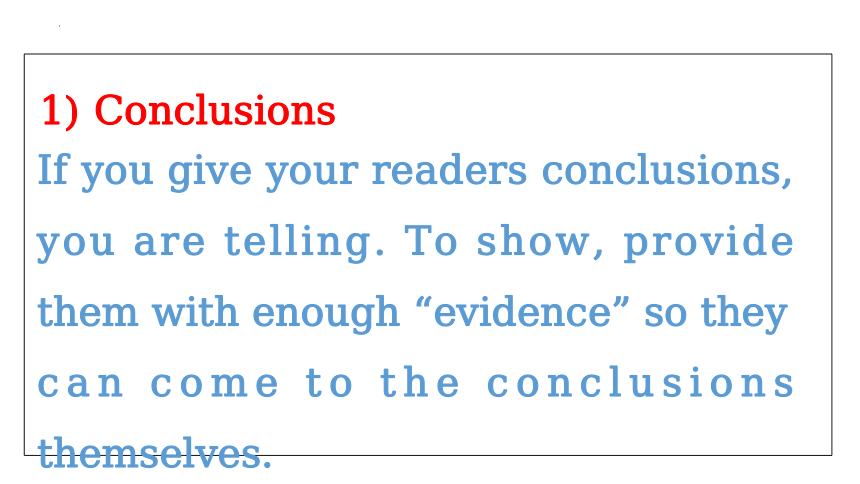

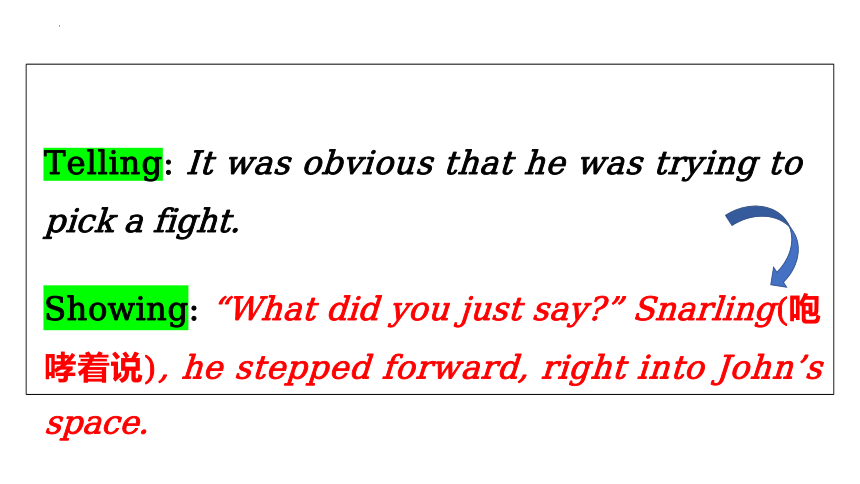

1) Conclusions

If you give your readers conclusions, you are telling. To show, provide them with enough “evidence” so they can come to the conclusions themselves.

Telling: It was obvious that he was trying to pick a fight.

Showing: “What did you just say ” Snarling(咆哮着说), he stepped forward, right into John’s space.

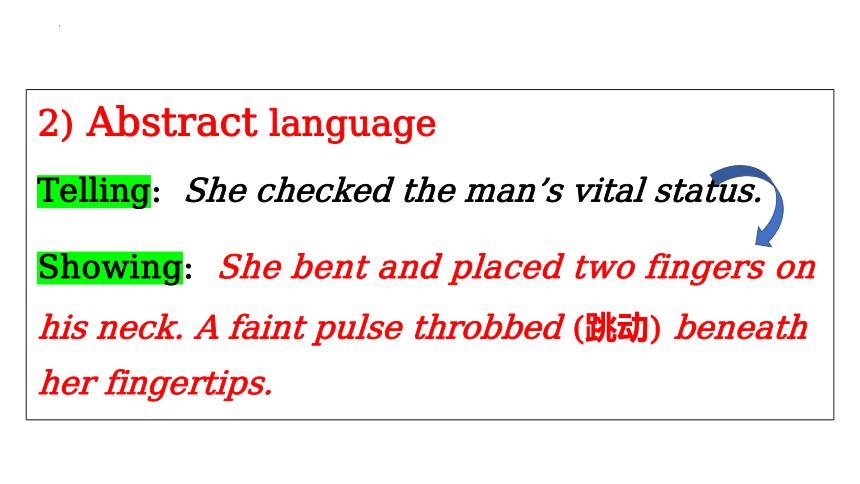

Telling: She checked the man’s vital status.

Showing: She bent and placed two fingers on his neck. A faint pulse throbbed (跳动) beneath her fingertips.

2) Abstract language

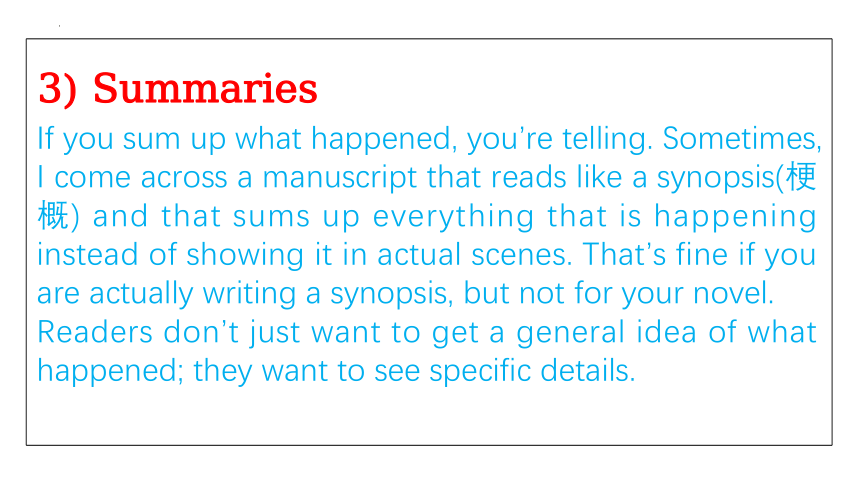

3) Summaries

If you sum up what happened, you’re telling. Sometimes, I come across a manuscript that reads like a synopsis(梗概) and that sums up everything that is happening instead of showing it in actual scenes. That’s fine if you are actually writing a synopsis, but not for your novel.

Readers don’t just want to get a general idea of what happened; they want to see specific details.

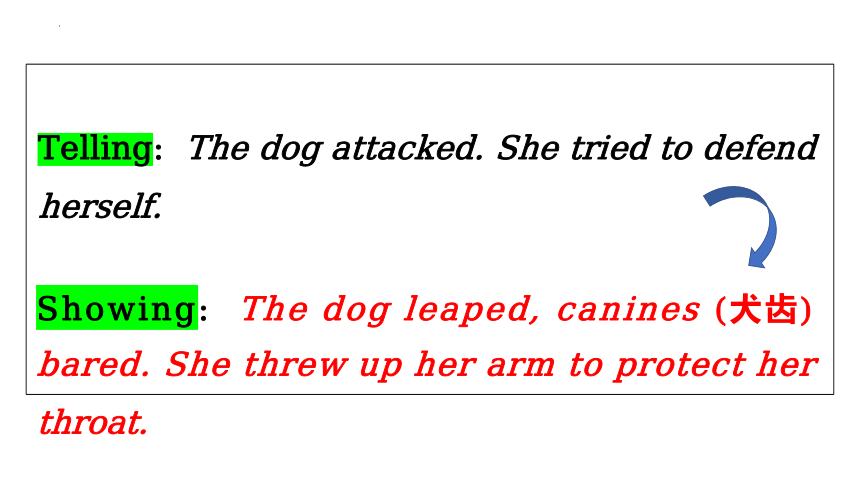

Telling: The dog attacked. She tried to defend herself.

Showing: The dog leaped, canines (犬齿) bared. She threw up her arm to protect her throat.

4) Backstories

If you report things that happened in the past, before this very moment, you are telling. For important scenes, show your readers what is happening as it’s happening, in real time, instead of summing up what happened a few minutes ago. A good indicator for when you might be reporting things that happened in the past is if you find yourself using the past perfect.

Telling: I had tested the car to see if it would start. It didn’t.

Showing: I turned the key in the ignition(点火开关). A click-click-click-click noise drifted up from the engine. I smashed my fist into the steering wheel. “Dammit!”

Telling: The dog tucked(把…藏入) its tail between its legs and whined (惨叫) anxiously.

Showing: The dog tucked its tail between its legs and whined.

5) Adverbs

If you find yourself using an adverb, you are usually telling. Whenever possible, cut the adverbs.

Telling: “Don’t lie to me,” she shouted angrily.

Showing: “Don’t lie to me, dammit.” She slammed her palm on the table.

Telling: Tina slowly walked down the street.

Showing: Tina strolled down the street.

Telling: I was afraid.

Showing: Oh God, oh God, oh God. My knees felt like squishy (湿软的) sponges as I fled down the stairs.

6) Adjectives

Like adverbs, adjectives can also be telling, especially if they are abstract adjectives such as interesting or beautiful .

Telling: It was cold.

Showing: She breathed into her hands to warm her numb fingers.

7) Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject with an adjective or noun. Examples are was/ were , is/ are, felt, appeared, seemed, looked . The problem with them is that they are weak, static(静态的) verbs that don’t show us an action. Replace most of them with more active verbs.

Telling: Tina felt tired.

Showing: She rubbed her eyes.

Telling: Tina seemed impressed.

Showing: Tina’s eyes widened, and her lips formed a silent, “Wow!”

Telling: Tina looked as if she was going to cry.

Showing: Tina’s bottom lip started to quiver.

Telling: When John left, Betty and Tina were relieved.

Showing: When the door closed behind John, Betty wiped her brow and Tina exhaled the breath she’d been holding.

8) Emotion Words

When you’re naming emotions, you are telling. Instead of naming emotions, use actions, thoughts, visceral(出自内心的) reactions, and body language to show what your characters are feeling.

9) Filters

Filter words are verbs that describe the character perceiving or thinking something, for example, saw, smelled, heard, felt, watched, noticed, realized, wondered and knew . The problem is that filter words tell your readers what the character perceives or thinks instead of letting them experience it directly. Readers are forced to watch the character from the outside instead of being in her head, experiencing things along with her.

Telling: Tina heard Betty suck in a breath.

Showing: Betty sucked in a breath.

Telling: Tina realized she had lost her keys.

Showing: Tina patted her pockets. Nothing. Oh shit . Where were her keys

The Art of Showing

How to turn telling into showing

1) Use the five senses

Showing means letting your readers experience your story world along with the point of view character. Try to engage all of your readers’ senses, not just sight. In every scene, put yourself in your POV character’s shoes and describe what he can see, hear, smell, taste, and sense.

I stuck my nose out of the car’s open window and breathed in the fresh pine scent. The cold air made my cheeks burn and my eyes tear.

2) Use strong, dynamic (动态的) verbs

Make your writing come to life by using strong, active verbs, not verbs that are weak and static. For example, instead of saying she walked , use she strutted(昂首阔步) , she strode(大步走) , she trudged(步履沉重地走) , or she tiptoed(踮着脚走) to show us exactly how she moves. Keep on the lookout for weak verbs—usually all forms of to be (including the overused there was and there were ) and to have —and replace them with verbs that paint a clearer picture in the reader’s mind.

Telling: The man was thin and wore a coat that was too big for him.

Showing: His coat hung around his frame.

Be careful not to overdo it, though. At times, you just want your characters to walk across a room, without drawing attention to it, instead of strutting, trudging, or tiptoeing. If the action is not that important, using a weaker verb is fine. But if you want to build suspense and tension, use the stronger verb to show what your character is feeling while she walks.

3) Use concrete nouns

Try to be as specific as possible rather than using generic(通用的) terms. That’s not just true for verbs, but for nouns too. Use concrete nouns that create the image you want in readers’ minds. Instead of having your characters eat breakfast, let your readers know that they’re having eggs and bacon.

Telling: Tina lived in a big house.

Showing: Tina’s steps echoed across the foyer(前厅) as she entered the mansion.

4) Break activities into smaller parts

One trick to write in a more concrete way is to break generic activities into smaller parts. Instead of telling us that your protagonist is cleaning, show us that she’s vacuuming and frowning at the sock she finds beneath the couch. Don’t overdo it, though. If the activity isn’t important, sum it up in a general sweep. But if it reveals something about the character—maybe how fastidious(有洁癖的) she is—or moves the plot forward, break it down into its parts. If she finds not a sock but drugs beneath her son’s bed, it might be worth showing your readers the details instead of just saying she was cleaning .

5) Use figurative language

One way to create images in readers’ minds and make your writing more vivid is the use of figurative language, especially similes(明喻) and metaphors(暗喻). A simile is a figure of speech that compares two things using the words like or as , e.g., her hair shone like gold. A metaphor compares two things more directly, e.g., the company was a gold mine.

Telling: Betty had callused(有茧子的) palms.

Showing: Betty’s palms felt like sandpaper.

6) Write in real time

Make sure you write in scenes and let the action unfold in real time. Instead of summing up what happened, let your readers witness the moment-to-moment action.

You don’t need to show everything in real time, of course; otherwise, your novel will be full of meaningless actions that will read like filler. Telling can be a great tool to compress the nonessential parts. It’s the important scenes—the ones that move the plot forward or reveal something about a character—that you want to show.

7) Use dialogue

One way to show the action in real time is to write dialogue. Dialogue is always showing—at least if you do it right.

8) Use internal monologue

Showing what your POV character is thinking can also help to reveal her emotions without having to name them.

Telling: I was relieved when my workday ended.

Showing: Finally, the bell rang, announcing the end of my workday. Thank the Lord .

9) Focus on actions and reactions

You have probably heard the saying actions speak louder than words . Just telling your readers that your character is a mean, bitter woman might not be enough for them to believe it. Showing her kick a puppy will immediately convince your readers that she’s mean.

Instead of telling your readers about your characters’ personality traits, let them get to know the characters through their actions.

Telling: Tina was a loyal friend. She always helped out whenever one of her acquaintances or family members needed her.

Showing: “Come on.” Tina patted her shoulder. “Assembling the furniture won’t be that bad. You know what they say about many hands.” She picked up the screwdriver.

Telling: Jake had always been a little clumsy.

Showing : When he reached out to pick up the saltshaker, he knocked over his wineglass.

Danger area 1

How to handle backstory

4. Telling readers what the characters feel (Emotions)

1. Telling readers about events that happened before the story began (Backstory)

2. Telling readers what the characters look like (Character descriptions)

3. Telling readers what the character experience through their senses (Setting descriptions)

Three danger areas for telling

Basically, backstory is everything that happened prior to page one of your book, for example, events from your character’s childhood or past relationships. Backstory is important because it shapes who your characters are today and how they will react to things that happen in the story.

DEFINITION OF BACKSTORY

▲ Backstory, especially if you introduce it too early, kills suspense .

THE PROBLEM WITH BACKSTORY

▲ Backstory isn’t story.

▲ Backstory is often dumped on readers much too soon .

▲ Backstory slows down the pacing .

Danger area 2

How to handle descriptions

▲ Avoid vague nouns and use specific ones instead.

▲ If you use adjectives, make sure they are descriptive ones.

▲ Use all five senses.

▲ Try not to rely on clichés in your descriptions.

▲ The best descriptions are dynamic, not static.

▲ Avoid large blocks of description.

DESCRIPTIONS OF SETTING

▲ The best descriptions are the ones that tell us more than just how the character looks but reveal something about his or her personality too.

▲ Readers don’t need to know every little detail about what the character looks like.

▲ Don’t describe your character all at once, in one large block of description.

DESCRIPTIONS OF CHARACTERS

▲ Avoid long lists of details .

▲ Use strong, dynamic verbs instead of static ones.

DESCRIPTIONS OF CHARACTERS

▲ Use dialogue.

Danger area 3

How to describe emotions

Telling and showing: She clapped her hands in delight.

Showing: She clapped her hands.

Telling and showing: Tina’s eyes narrowed angrily.

Showing : Tina’s eyes narrowed.

AVOID NAMING EMOTIONS

Don’t name emotions because that is telling.

Relief flooded Tina’s chest, making it hard for her to breathe.

Oh, thank God! She pressed her hand to her chest, trying to catch her breath.

EMOTION AS THE SUBJECT OF A SENTENCE

Don’t have to cut out all emotion words. Sometimes, when you use an emotion as the subject of a sentence and pair it with a strong verb, it can work—but only if you use this technique sparingly.

EIGHT WAYS TO REVEAL EMOTION WITHOUT TELLING

1) Physical responses

Emotions always trigger physical responses. When we are afraid, our hearts start racing, our palms become sweaty, and our muscles tense. These are involuntary, visceral(出自内心的) reactions that we have no control over. Make sure you describe physical sensations only for the POV character. If it’s a non-POV character experiencing a certain emotion, we can only see the outward physical responses, for example, trembling hands.

Telling: I was afraid.

Showing: Tremors wracked my body, and cold sweat trickled down my back.

Telling: She was angry.

Showing : Veins throbbed (抽动) in her temples.

2) Body language and actions

Body language is a great way to show what a character feels. Remember to use strong, dynamic verbs to convey the emotion.

Telling: Betty was elated(兴高采烈的).

Showing: Betty twirled(旋转), her arms spread wide as if to hug the entire world.

Telling: She was ashamed of her knobby(凸起的) knees.

Showing: She lowered her lashes(睫毛)and tugged her skirt over her knobby knees.

Telling: I looked at Betty with annoyance.

Showing : I glared at Betty.

3) Facial expressions

Facial expressions are another wonderful way to convey emotions, but remember that you can only use them for non-POV characters.

Telling: She was amused.

Showing: Her lips curled up in a smile.

Telling: She looked puzzled.

Showing: Her brow furrowed(皱眉), and her eyes rolled upward as if seeking answers from above.

4) Dialogue

Make sure you use dialogue to reveal what your characters are feeling. It’s a strong tool, since dialogue can—literally—speak for itself. If your characters are tense or angry, let them speak in shorter sentences and use words with harder sounds. If they are playful(嬉戏的) or in a reflective(沉思的) mood, make their sentences and words longer. And if your characters are nervous, they could stutter(结巴).

Telling: I was so angry at John.

Showing: I smashed my fist onto the desk. “Goddammit, John!”

Telling: She waited impatiently.

Showing : She tapped her foot. “Come on. I’m not getting any younger here.”

5) Internal monologue (thoughts)

Showing doesn’t mean that you can only write about external things such as actions and dialogue. You can—and should—also dive into your character’s mind. Internal monologue—or introspection(内省)—is another word for character thoughts. You can either present thoughts as direct internal monologue, written in first person and present tense and often set off by italics, or as indirect internal monologue in third person and past tense. Similar to when you’re writing dialogue, the character’s word choice can reveal his or her feelings.

Telling: She was confused.

Showing (indirect internal monologue) : What the hell was going on

Telling: She tried hard to hide how jealous she was of her brother.

Showing (direct internal monologue): She struggled to keep her face expressionless as her father patted Tom’s shoulder. Yeah, of course, Daddy’s golden child can do no wrong.

6) Setting descriptions

The words you choose to describe a setting from a character’s point of view can reveal a lot about what kind of mood he or she is in. The same setting can be seen in a different light, depending on what mood the POV character is in.

The weather or another part of the external setting can also mirror what your character is feeling.

Telling: It rained heavily.

Showing (revealing an upbeat mood) : Raindrops danced along the windowpane(窗玻璃).

Showing (revealing a pessimistic mood): Rain lashed(猛击) against the window.

7) The five senses

In moments of heightened(增强的) emotion, our senses can also become heightened, so we’re suddenly hyperaware of sounds or smells.

Telling: Afraid of whoever was following me, I walked faster.

Showing : Footsteps echoed behind me, and the stench(臭气) of stale(难闻的) beer hit my nose. I walked faster.

8) Figurative language

Metaphors, similes, and other imagery can also be an effective way to reveal character emotions.

Telling: She stared at him aggressively.

Showing : She stared at him like a prizefighter(职业拳击手) sizing up (打量)an opponent.

Telling in dialogue

How to recognize and fix it

1) Maid-and-butler dialogue

Maid-and-butler dialogue, also called “as you know, Bob” dialogue, is a form of info-dumping through dialogue. The author wants to reveal some information to the reader, so he or she has the characters tell each other about that information, even though they both know about it already and have no reason to talk about it.

“As you know, Bob, the master is away on business in London with his oldest son…”

2) “Creative” dialogue tags

Some authors seem to think that readers will get bored with said as a dialogue tag, so they try to come up with more creative dialogue tags such as exclaimed (惊叫), demanded , or commented .

Normally, variety and creativity are good things when you’re a writer, but this is an exception. The best dialogue tag is always said because it’s unobtrusive (不引人注目的) and doesn’t distract from the dialogue itself.

If you use dialogue tags other than said (or maybe asked and answered), you’re telling. Avoid dialogue tags that explain the dialogue to your readers and let the dialogue speak for itself.

Telling: “Can’t keep up with me ” she teased.

Showing : “Can’t keep up with me, old woman ”

Telling: “It wasn’t him. It was me,” I confessed.

Showing : “It wasn’t him,” I said. “It was me.”

3) Adverbs in dialogue tags

Using adverbs in dialogue tags is a form of telling too. The emotion should be visible in the dialogue itself, and it can also be revealed through body language and facial expressions, so you don’t need the adverb.

Telling: “Isn’t my garden beautiful ” she said smugly(自鸣得意地).

Showing : “That’s one fine looking garden, isn’t it ” She polished her nails on her shirt.

Telling: “Get out,” I said angrily.

Showing : “Get out.” I shoved him toward the door.

Telling: “It wasn’t him. It was me,” I confessed.

Showing : “It wasn’t him,” I said. “It was me.”

4) Reported dialogue

Reported dialogue—sometimes called indirect dialogue—is when you, the author, are telling your readers what one character said without showing the actual words in quotation marks. Most often, you should avoid reported dialogue since it’s another form of telling.

Telling: Tina explained that she hadn’t seen him in a while.

Showing : “I haven’t seen him in a while,” Tina said.

Telling: Tina asked how often they went to the zoo.

Showing : “How often do you go to the zoo ” Tina asked.

If the conversation is important, show it. And if it’s not important because it doesn’t move your plot forward, cut it.

The uses of telling

How to recognize and fix it When telling is the better choice

1) Unimportant details

When you compare the telling examples with the ones that show, you probably realize that showing takes up more space on the page. The more space you give to something in your story, the more important it will seem. Showing is a signal to readers that what you’re writing about is important, so they’d better pay attention. If you show everything, readers will assume everything is important and they’ll eventually become exhausted. The really important things won’t stand out anymore.

Showing: I moved my mouse to the top-right corner of the screen and clicked on the X icon to close the browser.

Telling : I closed the browser.

2) Transitions

Telling can be useful for transitions between scenes, when you are jumping ahead in time, switch point of view, or jump to another location. You can use telling to summarize a span of time or distance and debrief(汇报) your readers on what happened in between the scenes.

After three days without a call from John, Tina had enough.

You can use telling for transitions not just at the beginning, but at the end of a scene too. Telling helps to move your readers into or out of scenes.

Betty locked her apartment door and went to work.

“Went to work” is telling. Unless something exciting, for example, an accident, happens on the way to work, you don’t need to show the car ride. Sum it up by telling readers that she went to work.

Exercises

Telling: She was cold.

Showing : Her teeth chattered as she blew on her fingers.

Telling: It was hot outside.

Showing : Heat sizzled(发出咝咝声) from the pavement. She wiped her sweaty brow and tried not to gag(作呕) at the stench of rotting garbage on the sidewalks.

Telling: “Get out,” I said angrily.

Showing : “Get out.” I shoved him toward the door.

Telling: He looked tired.

Showing : He slumped(重重地坐下) into his chair. His eyelids drooped(低垂), and his chin sank on his chest.

Telling: She was overweight.

Showing : As she heaved (用力拖) herself up from her chair, Jake halfway expected to hear a groan of relief from the piece of furniture.

Telling: The house was run-down(破败的).

Showing : Paint flaked(剥落) from the walls. Weeds had taken over the cracks in the driveway. The smell of mold (霉) and urine filled Tina’s nostrils as she stepped over broken glass.

Telling: It was a dark and stormy night.

Showing : The wind rattled(发出格格声) the shutters(护窗) and hurled(猛摔) rain from the night sky.

Telling: She seemed uncomfortable.

Showing : She slid to the edge of her seat and shuffled(拖着脚走) her feet beneath the table.

Telling: He was helpless.

Showing : He rubbed his temples. What was he supposed to do now

Telling: It was raining as she drove.

Showing : Rain drummed on the windshield and the Honda’s roof, drowning out the hum of the engine.

Telling: I ate dinner.

Showing : I cut into her juicy steak. The scent of herb butter teased my nose.

Telling: The pizza looked delicious, but it tasted horrible.

Showing : Steam rising up off the melted cheese made his mouth water. He picked up a slice and took a huge bite. A bitter taste spread across his tongue. Ugh. Dammit. Who the hell had put olives on his pizza

Telling: She was afraid.

Showing : She wrapped her arms around herself and wiped her palms, wet with perspiration, on the back of her shirt.

Telling: She was curious.

Showing : She tilted her head to the side and waved her hand in a gimme motion. “Come on. Tell me!”

Telling: Tina was a spoiled child.

Showing : Tina threw herself on the floor and flailed(乱动) her arms and legs. “I want it! I want it! I want it!”

Telling: When her brother refused to give her the book, she became angry.

Showing : Blood roared in her ears. She thrust(猛推) her chin forward. “If you don’t give me that damn book back, I’ll kill you.”

Telling: Satisfied that everything was packed, Tina grabbed her bag.

Showing : Great. Everything was packed. Tina grabbed her bag.

Show, Don’t Tell

How to write vivid descriptions, handle backstory, and describe your characters’ emotions

Definition

What show, don’t tell means

Telling Showing

means that you—the author—give your readers conclusions and interpretations; you tell them what to think instead of letting them think for themselves. means that you provide your readers with enough concrete, vivid details so that they can draw their own conclusions.

is like giving readers a secondhand report afterward. lets readers experience the events firsthand, through the five senses of the character.

is like reading about an accident in the newspaper the day after it happened. is like witnessing the accident the moment it happens, hearing the screech(尖锐刺耳的声音) of the metal and the screams of the injured.

Telling Showing

summarizes events that happened in the past or gives general statements that don’t happen at any specific time. lets readers witness events in real time, in actual scenes with action and dialogue. We stay in the present, firmly rooted in the POV character’s experience.

is abstract. creates a concrete, specific picture in the reader’s mind.

gives you facts. evokes (唤起) emotions.

Telling Showing

is also called narrative summary. is dramatization.

distances readers from the events in the story and from the characters and makes them passive recipients (接受者) of information. involves readers in the story and makes them active participants.

AN EXAMPLE

Telling: Tina was angry.

Showing: Tina slammed the door shut and stormed into the kitchen. “What the hell were you thinking ”

Nine red flags for telling

How to tell when you’re telling

1) Conclusions

If you give your readers conclusions, you are telling. To show, provide them with enough “evidence” so they can come to the conclusions themselves.

Telling: It was obvious that he was trying to pick a fight.

Showing: “What did you just say ” Snarling(咆哮着说), he stepped forward, right into John’s space.

Telling: She checked the man’s vital status.

Showing: She bent and placed two fingers on his neck. A faint pulse throbbed (跳动) beneath her fingertips.

2) Abstract language

3) Summaries

If you sum up what happened, you’re telling. Sometimes, I come across a manuscript that reads like a synopsis(梗概) and that sums up everything that is happening instead of showing it in actual scenes. That’s fine if you are actually writing a synopsis, but not for your novel.

Readers don’t just want to get a general idea of what happened; they want to see specific details.

Telling: The dog attacked. She tried to defend herself.

Showing: The dog leaped, canines (犬齿) bared. She threw up her arm to protect her throat.

4) Backstories

If you report things that happened in the past, before this very moment, you are telling. For important scenes, show your readers what is happening as it’s happening, in real time, instead of summing up what happened a few minutes ago. A good indicator for when you might be reporting things that happened in the past is if you find yourself using the past perfect.

Telling: I had tested the car to see if it would start. It didn’t.

Showing: I turned the key in the ignition(点火开关). A click-click-click-click noise drifted up from the engine. I smashed my fist into the steering wheel. “Dammit!”

Telling: The dog tucked(把…藏入) its tail between its legs and whined (惨叫) anxiously.

Showing: The dog tucked its tail between its legs and whined.

5) Adverbs

If you find yourself using an adverb, you are usually telling. Whenever possible, cut the adverbs.

Telling: “Don’t lie to me,” she shouted angrily.

Showing: “Don’t lie to me, dammit.” She slammed her palm on the table.

Telling: Tina slowly walked down the street.

Showing: Tina strolled down the street.

Telling: I was afraid.

Showing: Oh God, oh God, oh God. My knees felt like squishy (湿软的) sponges as I fled down the stairs.

6) Adjectives

Like adverbs, adjectives can also be telling, especially if they are abstract adjectives such as interesting or beautiful .

Telling: It was cold.

Showing: She breathed into her hands to warm her numb fingers.

7) Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject with an adjective or noun. Examples are was/ were , is/ are, felt, appeared, seemed, looked . The problem with them is that they are weak, static(静态的) verbs that don’t show us an action. Replace most of them with more active verbs.

Telling: Tina felt tired.

Showing: She rubbed her eyes.

Telling: Tina seemed impressed.

Showing: Tina’s eyes widened, and her lips formed a silent, “Wow!”

Telling: Tina looked as if she was going to cry.

Showing: Tina’s bottom lip started to quiver.

Telling: When John left, Betty and Tina were relieved.

Showing: When the door closed behind John, Betty wiped her brow and Tina exhaled the breath she’d been holding.

8) Emotion Words

When you’re naming emotions, you are telling. Instead of naming emotions, use actions, thoughts, visceral(出自内心的) reactions, and body language to show what your characters are feeling.

9) Filters

Filter words are verbs that describe the character perceiving or thinking something, for example, saw, smelled, heard, felt, watched, noticed, realized, wondered and knew . The problem is that filter words tell your readers what the character perceives or thinks instead of letting them experience it directly. Readers are forced to watch the character from the outside instead of being in her head, experiencing things along with her.

Telling: Tina heard Betty suck in a breath.

Showing: Betty sucked in a breath.

Telling: Tina realized she had lost her keys.

Showing: Tina patted her pockets. Nothing. Oh shit . Where were her keys

The Art of Showing

How to turn telling into showing

1) Use the five senses

Showing means letting your readers experience your story world along with the point of view character. Try to engage all of your readers’ senses, not just sight. In every scene, put yourself in your POV character’s shoes and describe what he can see, hear, smell, taste, and sense.

I stuck my nose out of the car’s open window and breathed in the fresh pine scent. The cold air made my cheeks burn and my eyes tear.

2) Use strong, dynamic (动态的) verbs

Make your writing come to life by using strong, active verbs, not verbs that are weak and static. For example, instead of saying she walked , use she strutted(昂首阔步) , she strode(大步走) , she trudged(步履沉重地走) , or she tiptoed(踮着脚走) to show us exactly how she moves. Keep on the lookout for weak verbs—usually all forms of to be (including the overused there was and there were ) and to have —and replace them with verbs that paint a clearer picture in the reader’s mind.

Telling: The man was thin and wore a coat that was too big for him.

Showing: His coat hung around his frame.

Be careful not to overdo it, though. At times, you just want your characters to walk across a room, without drawing attention to it, instead of strutting, trudging, or tiptoeing. If the action is not that important, using a weaker verb is fine. But if you want to build suspense and tension, use the stronger verb to show what your character is feeling while she walks.

3) Use concrete nouns

Try to be as specific as possible rather than using generic(通用的) terms. That’s not just true for verbs, but for nouns too. Use concrete nouns that create the image you want in readers’ minds. Instead of having your characters eat breakfast, let your readers know that they’re having eggs and bacon.

Telling: Tina lived in a big house.

Showing: Tina’s steps echoed across the foyer(前厅) as she entered the mansion.

4) Break activities into smaller parts

One trick to write in a more concrete way is to break generic activities into smaller parts. Instead of telling us that your protagonist is cleaning, show us that she’s vacuuming and frowning at the sock she finds beneath the couch. Don’t overdo it, though. If the activity isn’t important, sum it up in a general sweep. But if it reveals something about the character—maybe how fastidious(有洁癖的) she is—or moves the plot forward, break it down into its parts. If she finds not a sock but drugs beneath her son’s bed, it might be worth showing your readers the details instead of just saying she was cleaning .

5) Use figurative language

One way to create images in readers’ minds and make your writing more vivid is the use of figurative language, especially similes(明喻) and metaphors(暗喻). A simile is a figure of speech that compares two things using the words like or as , e.g., her hair shone like gold. A metaphor compares two things more directly, e.g., the company was a gold mine.

Telling: Betty had callused(有茧子的) palms.

Showing: Betty’s palms felt like sandpaper.

6) Write in real time

Make sure you write in scenes and let the action unfold in real time. Instead of summing up what happened, let your readers witness the moment-to-moment action.

You don’t need to show everything in real time, of course; otherwise, your novel will be full of meaningless actions that will read like filler. Telling can be a great tool to compress the nonessential parts. It’s the important scenes—the ones that move the plot forward or reveal something about a character—that you want to show.

7) Use dialogue

One way to show the action in real time is to write dialogue. Dialogue is always showing—at least if you do it right.

8) Use internal monologue

Showing what your POV character is thinking can also help to reveal her emotions without having to name them.

Telling: I was relieved when my workday ended.

Showing: Finally, the bell rang, announcing the end of my workday. Thank the Lord .

9) Focus on actions and reactions

You have probably heard the saying actions speak louder than words . Just telling your readers that your character is a mean, bitter woman might not be enough for them to believe it. Showing her kick a puppy will immediately convince your readers that she’s mean.

Instead of telling your readers about your characters’ personality traits, let them get to know the characters through their actions.

Telling: Tina was a loyal friend. She always helped out whenever one of her acquaintances or family members needed her.

Showing: “Come on.” Tina patted her shoulder. “Assembling the furniture won’t be that bad. You know what they say about many hands.” She picked up the screwdriver.

Telling: Jake had always been a little clumsy.

Showing : When he reached out to pick up the saltshaker, he knocked over his wineglass.

Danger area 1

How to handle backstory

4. Telling readers what the characters feel (Emotions)

1. Telling readers about events that happened before the story began (Backstory)

2. Telling readers what the characters look like (Character descriptions)

3. Telling readers what the character experience through their senses (Setting descriptions)

Three danger areas for telling

Basically, backstory is everything that happened prior to page one of your book, for example, events from your character’s childhood or past relationships. Backstory is important because it shapes who your characters are today and how they will react to things that happen in the story.

DEFINITION OF BACKSTORY

▲ Backstory, especially if you introduce it too early, kills suspense .

THE PROBLEM WITH BACKSTORY

▲ Backstory isn’t story.

▲ Backstory is often dumped on readers much too soon .

▲ Backstory slows down the pacing .

Danger area 2

How to handle descriptions

▲ Avoid vague nouns and use specific ones instead.

▲ If you use adjectives, make sure they are descriptive ones.

▲ Use all five senses.

▲ Try not to rely on clichés in your descriptions.

▲ The best descriptions are dynamic, not static.

▲ Avoid large blocks of description.

DESCRIPTIONS OF SETTING

▲ The best descriptions are the ones that tell us more than just how the character looks but reveal something about his or her personality too.

▲ Readers don’t need to know every little detail about what the character looks like.

▲ Don’t describe your character all at once, in one large block of description.

DESCRIPTIONS OF CHARACTERS

▲ Avoid long lists of details .

▲ Use strong, dynamic verbs instead of static ones.

DESCRIPTIONS OF CHARACTERS

▲ Use dialogue.

Danger area 3

How to describe emotions

Telling and showing: She clapped her hands in delight.

Showing: She clapped her hands.

Telling and showing: Tina’s eyes narrowed angrily.

Showing : Tina’s eyes narrowed.

AVOID NAMING EMOTIONS

Don’t name emotions because that is telling.

Relief flooded Tina’s chest, making it hard for her to breathe.

Oh, thank God! She pressed her hand to her chest, trying to catch her breath.

EMOTION AS THE SUBJECT OF A SENTENCE

Don’t have to cut out all emotion words. Sometimes, when you use an emotion as the subject of a sentence and pair it with a strong verb, it can work—but only if you use this technique sparingly.

EIGHT WAYS TO REVEAL EMOTION WITHOUT TELLING

1) Physical responses

Emotions always trigger physical responses. When we are afraid, our hearts start racing, our palms become sweaty, and our muscles tense. These are involuntary, visceral(出自内心的) reactions that we have no control over. Make sure you describe physical sensations only for the POV character. If it’s a non-POV character experiencing a certain emotion, we can only see the outward physical responses, for example, trembling hands.

Telling: I was afraid.

Showing: Tremors wracked my body, and cold sweat trickled down my back.

Telling: She was angry.

Showing : Veins throbbed (抽动) in her temples.

2) Body language and actions

Body language is a great way to show what a character feels. Remember to use strong, dynamic verbs to convey the emotion.

Telling: Betty was elated(兴高采烈的).

Showing: Betty twirled(旋转), her arms spread wide as if to hug the entire world.

Telling: She was ashamed of her knobby(凸起的) knees.

Showing: She lowered her lashes(睫毛)and tugged her skirt over her knobby knees.

Telling: I looked at Betty with annoyance.

Showing : I glared at Betty.

3) Facial expressions

Facial expressions are another wonderful way to convey emotions, but remember that you can only use them for non-POV characters.

Telling: She was amused.

Showing: Her lips curled up in a smile.

Telling: She looked puzzled.

Showing: Her brow furrowed(皱眉), and her eyes rolled upward as if seeking answers from above.

4) Dialogue

Make sure you use dialogue to reveal what your characters are feeling. It’s a strong tool, since dialogue can—literally—speak for itself. If your characters are tense or angry, let them speak in shorter sentences and use words with harder sounds. If they are playful(嬉戏的) or in a reflective(沉思的) mood, make their sentences and words longer. And if your characters are nervous, they could stutter(结巴).

Telling: I was so angry at John.

Showing: I smashed my fist onto the desk. “Goddammit, John!”

Telling: She waited impatiently.

Showing : She tapped her foot. “Come on. I’m not getting any younger here.”

5) Internal monologue (thoughts)

Showing doesn’t mean that you can only write about external things such as actions and dialogue. You can—and should—also dive into your character’s mind. Internal monologue—or introspection(内省)—is another word for character thoughts. You can either present thoughts as direct internal monologue, written in first person and present tense and often set off by italics, or as indirect internal monologue in third person and past tense. Similar to when you’re writing dialogue, the character’s word choice can reveal his or her feelings.

Telling: She was confused.

Showing (indirect internal monologue) : What the hell was going on

Telling: She tried hard to hide how jealous she was of her brother.

Showing (direct internal monologue): She struggled to keep her face expressionless as her father patted Tom’s shoulder. Yeah, of course, Daddy’s golden child can do no wrong.

6) Setting descriptions

The words you choose to describe a setting from a character’s point of view can reveal a lot about what kind of mood he or she is in. The same setting can be seen in a different light, depending on what mood the POV character is in.

The weather or another part of the external setting can also mirror what your character is feeling.

Telling: It rained heavily.

Showing (revealing an upbeat mood) : Raindrops danced along the windowpane(窗玻璃).

Showing (revealing a pessimistic mood): Rain lashed(猛击) against the window.

7) The five senses

In moments of heightened(增强的) emotion, our senses can also become heightened, so we’re suddenly hyperaware of sounds or smells.

Telling: Afraid of whoever was following me, I walked faster.

Showing : Footsteps echoed behind me, and the stench(臭气) of stale(难闻的) beer hit my nose. I walked faster.

8) Figurative language

Metaphors, similes, and other imagery can also be an effective way to reveal character emotions.

Telling: She stared at him aggressively.

Showing : She stared at him like a prizefighter(职业拳击手) sizing up (打量)an opponent.

Telling in dialogue

How to recognize and fix it

1) Maid-and-butler dialogue

Maid-and-butler dialogue, also called “as you know, Bob” dialogue, is a form of info-dumping through dialogue. The author wants to reveal some information to the reader, so he or she has the characters tell each other about that information, even though they both know about it already and have no reason to talk about it.

“As you know, Bob, the master is away on business in London with his oldest son…”

2) “Creative” dialogue tags

Some authors seem to think that readers will get bored with said as a dialogue tag, so they try to come up with more creative dialogue tags such as exclaimed (惊叫), demanded , or commented .

Normally, variety and creativity are good things when you’re a writer, but this is an exception. The best dialogue tag is always said because it’s unobtrusive (不引人注目的) and doesn’t distract from the dialogue itself.

If you use dialogue tags other than said (or maybe asked and answered), you’re telling. Avoid dialogue tags that explain the dialogue to your readers and let the dialogue speak for itself.

Telling: “Can’t keep up with me ” she teased.

Showing : “Can’t keep up with me, old woman ”

Telling: “It wasn’t him. It was me,” I confessed.

Showing : “It wasn’t him,” I said. “It was me.”

3) Adverbs in dialogue tags

Using adverbs in dialogue tags is a form of telling too. The emotion should be visible in the dialogue itself, and it can also be revealed through body language and facial expressions, so you don’t need the adverb.

Telling: “Isn’t my garden beautiful ” she said smugly(自鸣得意地).

Showing : “That’s one fine looking garden, isn’t it ” She polished her nails on her shirt.

Telling: “Get out,” I said angrily.

Showing : “Get out.” I shoved him toward the door.

Telling: “It wasn’t him. It was me,” I confessed.

Showing : “It wasn’t him,” I said. “It was me.”

4) Reported dialogue

Reported dialogue—sometimes called indirect dialogue—is when you, the author, are telling your readers what one character said without showing the actual words in quotation marks. Most often, you should avoid reported dialogue since it’s another form of telling.

Telling: Tina explained that she hadn’t seen him in a while.

Showing : “I haven’t seen him in a while,” Tina said.

Telling: Tina asked how often they went to the zoo.

Showing : “How often do you go to the zoo ” Tina asked.

If the conversation is important, show it. And if it’s not important because it doesn’t move your plot forward, cut it.

The uses of telling

How to recognize and fix it When telling is the better choice

1) Unimportant details

When you compare the telling examples with the ones that show, you probably realize that showing takes up more space on the page. The more space you give to something in your story, the more important it will seem. Showing is a signal to readers that what you’re writing about is important, so they’d better pay attention. If you show everything, readers will assume everything is important and they’ll eventually become exhausted. The really important things won’t stand out anymore.

Showing: I moved my mouse to the top-right corner of the screen and clicked on the X icon to close the browser.

Telling : I closed the browser.

2) Transitions

Telling can be useful for transitions between scenes, when you are jumping ahead in time, switch point of view, or jump to another location. You can use telling to summarize a span of time or distance and debrief(汇报) your readers on what happened in between the scenes.

After three days without a call from John, Tina had enough.

You can use telling for transitions not just at the beginning, but at the end of a scene too. Telling helps to move your readers into or out of scenes.

Betty locked her apartment door and went to work.

“Went to work” is telling. Unless something exciting, for example, an accident, happens on the way to work, you don’t need to show the car ride. Sum it up by telling readers that she went to work.

Exercises

Telling: She was cold.

Showing : Her teeth chattered as she blew on her fingers.

Telling: It was hot outside.

Showing : Heat sizzled(发出咝咝声) from the pavement. She wiped her sweaty brow and tried not to gag(作呕) at the stench of rotting garbage on the sidewalks.

Telling: “Get out,” I said angrily.

Showing : “Get out.” I shoved him toward the door.

Telling: He looked tired.

Showing : He slumped(重重地坐下) into his chair. His eyelids drooped(低垂), and his chin sank on his chest.

Telling: She was overweight.

Showing : As she heaved (用力拖) herself up from her chair, Jake halfway expected to hear a groan of relief from the piece of furniture.

Telling: The house was run-down(破败的).

Showing : Paint flaked(剥落) from the walls. Weeds had taken over the cracks in the driveway. The smell of mold (霉) and urine filled Tina’s nostrils as she stepped over broken glass.

Telling: It was a dark and stormy night.

Showing : The wind rattled(发出格格声) the shutters(护窗) and hurled(猛摔) rain from the night sky.

Telling: She seemed uncomfortable.

Showing : She slid to the edge of her seat and shuffled(拖着脚走) her feet beneath the table.

Telling: He was helpless.

Showing : He rubbed his temples. What was he supposed to do now

Telling: It was raining as she drove.

Showing : Rain drummed on the windshield and the Honda’s roof, drowning out the hum of the engine.

Telling: I ate dinner.

Showing : I cut into her juicy steak. The scent of herb butter teased my nose.

Telling: The pizza looked delicious, but it tasted horrible.

Showing : Steam rising up off the melted cheese made his mouth water. He picked up a slice and took a huge bite. A bitter taste spread across his tongue. Ugh. Dammit. Who the hell had put olives on his pizza

Telling: She was afraid.

Showing : She wrapped her arms around herself and wiped her palms, wet with perspiration, on the back of her shirt.

Telling: She was curious.

Showing : She tilted her head to the side and waved her hand in a gimme motion. “Come on. Tell me!”

Telling: Tina was a spoiled child.

Showing : Tina threw herself on the floor and flailed(乱动) her arms and legs. “I want it! I want it! I want it!”

Telling: When her brother refused to give her the book, she became angry.

Showing : Blood roared in her ears. She thrust(猛推) her chin forward. “If you don’t give me that damn book back, I’ll kill you.”

Telling: Satisfied that everything was packed, Tina grabbed her bag.

Showing : Great. Everything was packed. Tina grabbed her bag.